Mysterious flooded cities, hiding just below the water’s surface, have intrigued storytellers and researchers around the world for centuries. Whether it’s the quest to find the lost civilization of Atlantis, or searching lakes for signs of ancient human inhabitation, we’re fascinated by communities sunken into a watery grave. Many people, even locals, are unaware that southeastern Ontario has its own collection of hidden treasures, entire communities flooded in one of the busiest waterways in eastern North America. Although the flooding was planned, plenty of mystery surrounds the Lost Villages of the St. Lawrence River.

Building Historic Communities

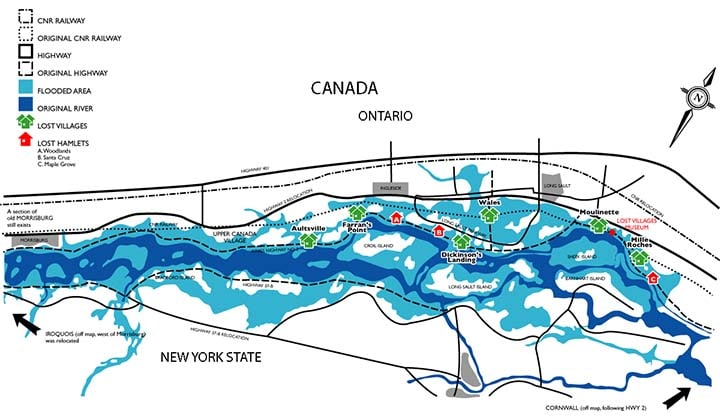

The St. Lawrence valley in southeastern Ontario was once lined with homesteads and farms that hugged the historic waterway. The landscape was dotted with small towns, villages, and hamlets, including places like Aultsville, Moulinette, and Wales. Migrants from eastern and central Canada were joined by people from around the world and together they formed thriving communities.

The settlements were hubs of activity for the growing agricultural industries in the valley. Gradually, industrial interest in the area grew, as entrepreneurs sought to harness the water resources and electric power potential along the vast waterway. Soon the farmers were joined by industrialists and the entire valley boomed in the late 19th century. The small communities were quickly put on the map and even one of Ontario’s premiers hailed from the area. Although the population grew, the stretch between the small cities of Cornwall and Brockville remained a collection of small communities, often home to multi-generational families who shared a love of the land.

A Plan to Quell Nature

When some of the first European explorers came down the St. Lawrence River, they noted many places of rough passage on their maps. There were shallow sections, rapids, narrow channels and unexpected islands that would poke out during low water levels. Navigation, particularly between modern-day Cornwall and Kingston, was difficult and very dangerous, resulting in a huge collection of sunken ships. Even during those early days of exploration, European settlers dreamt of a broad navigable waterway that could connect to the Atlantic Ocean to the east with the interior of the continent to the west.

That dream was gradually undertaken throughout the 19th century. Canals, locks, safe passageways, lighthouses, dams and other infrastructure were slowly built along the waterway. However, the size and type of ship able to safely pass was restricted and the route was notoriously slow and cumbersome. For example, passengers travelling by steamship had to transfer to a specially-designed “rapid ship” that would bring them safely along the most treacherous waters at Long Sault. The journey was dangerous and inconvenient, but also thrilling for people on board.

By the early 20th century, Canada and the United States were locked in negotiations about how the St. Lawrence could be redeveloped as a deep and navigable waterway for modern ships. The project would open up shipping from the Atlantic Ocean all the way through the Great Lakes system, terminating thousands of kilometers away in Minnesota. Although both countries were eager to see the project completed, it was a diplomatic nightmare. With the St. Lawrence River forming the border between the two nations, it took decades and many successive governments to finally come to an agreement.

When the flooding plan was outlined, there was a massive cry of protest from the local residents. The plans, which included the construction of a huge dam to control water levels, called for the flooding of entire communities, huge tracts of agricultural lands, and a complete transformation of the environment. Opposition was fierce, particularly from generations of families who made a living along the river. Despite fiery protests and strongly worded pleas to the government, the St. Lawrence Seaway was approved and went ahead as planned. The seaway project became one of the largest and most ambitious waterway projects of its time.

Upcoming Paranormal Investigations at The Lost Villages Museum!

Flooding the Villages

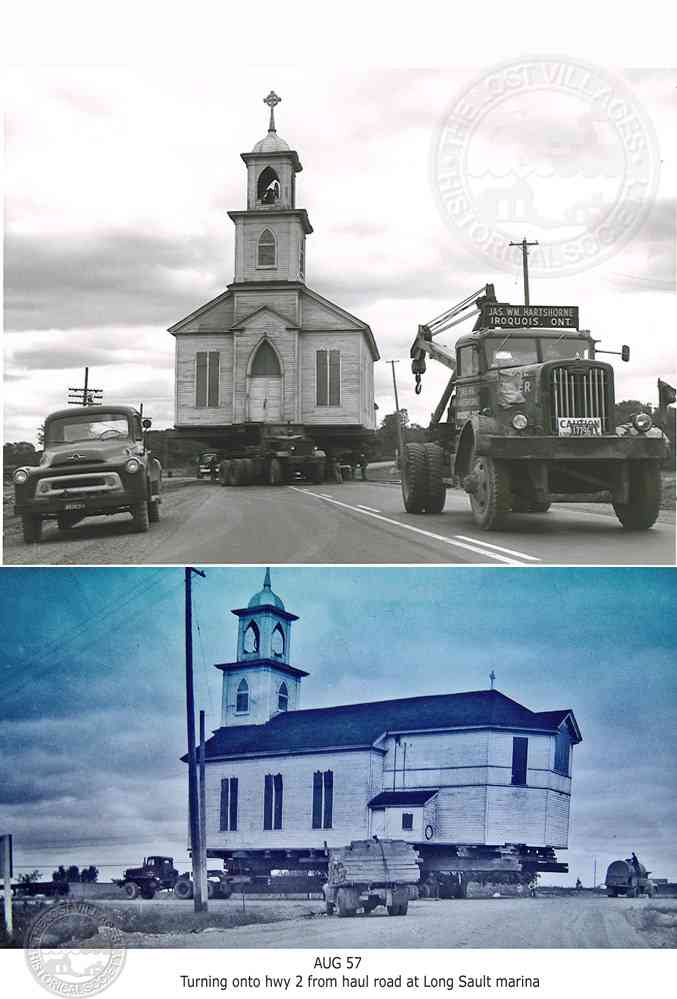

On July 1 1958, now known locally as “inundation day”, the flooding began. But there was a lot of preparation that preceded the momentous event. First, numerous communities had to be emptied and nearly 7,000 residents had to be relocated. Hundreds of buildings were moved in one of the largest community relocations of its time. Buildings were lifted off their foundations and placed onto trucks, and then slowly pulled to their new locations. But most buildings were scheduled to be demolished and families were minimally compensated for the property loss. Many residents at the time noted that the monetary compensation only covered their physical costs and the emotional and mental toll was never addressed. After the displacement, some families continued to live in the St. Lawrence area, determined to establish new communities, but others couldn’t face the traumatic memories and chose to leave the area altogether.

With the planned disappearance of so many communities, some people decided to take advantage of rare opportunities. For example, it was decided that a fire experiment would be conducted on the community of Aultsville. Shortly before the flooding, after some community buildings had been removed, the old town was deliberately set alight. Scientists were present to study how fires started within a structure and travelled from building to building, hoping to determine the best ways for combatting large and complex fires. But many community members were there too, watching their beloved buildings go up in flames. While many have since praised the Aultsville fire as a ground-breaking moment for research, others continue to recount the trauma of seeing their community burn to the ground.

Early in the morning on July 1, the dam was operational and the waters of the St. Lawrence River slowly began to rise. Some residents turned out to witness the eerie scene as the waters of the St. Lawrence slowly covered the roads they had walked on for years and overcame the foundations of where they once called home. After four days of flooding, the water lapped at new shorelines and “Lake St. Lawrence” was officially created. The following year the seaway was completed, and Queen Elizabeth attended the inauguration. The opening of the seaway, with all of its innovation, was hailed as an engineering marvel that would transform transportation and shipping in central North America.

Remembering What Was Lost

When the seaway was flooded, numerous ecological features were lost. The wetlands that had characterized the shorelines for countless generations were disrupted, some species of fish went nearly extinct and invasive species have gradually worked their way into the ecosystem. The grand rapids that had attracted so many people to the area for millennia were gone, the water now eerily calmed.

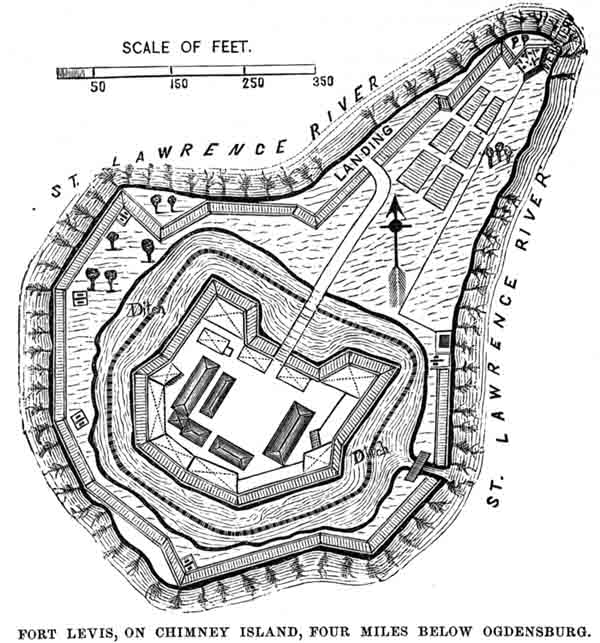

Before the flooding, there were numerous islands dotting the middle of the river; now they were shrunk or completely lost. One flooded island was historically known as Isle Royale (later Fort Levis), established by the French in the late 1700s. The fort was an important line of defense in the middle of the St Lawrence, now located near present-day Prescott. It was a final stronghold for the French before they surrendered to the British in 1760. The basic outline of the fort was still visible before the seaway was flooded and you can still see a tiny portion of the high ground poking up above the surface of the river. It’s likely that archaeological deposits are still below the water’s surface to this day.

In fact, the flooding of the St Lawrence River transformed the area into a widely renowned spot for scuba diving. People from all over the world come to explore the many shipwrecks which have occurred over the years. But others come specifically to look at the remnants of the lost villages. Sometimes you don’t need to dip your head below water to see the ghostly evidence. Some streets, foundations and community markers are visible when the water is clear and, when the levels are seasonably low, parts of the old villages are exposed to the fresh air once again.

The Lost Villages Museum and Upper Canada Village

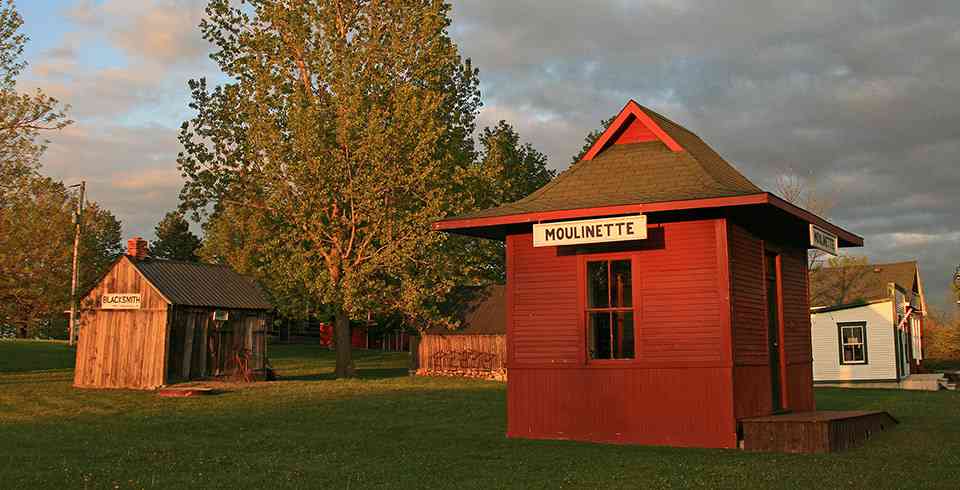

Some of the buildings from the lost villages were relocated to two open air museums: the Lost Villages Museum near Long Sault and Upper Canada Village near Morrisburg. The Lost Villages Museum tells the story of the communities and residents that existed prior to the flooding. The museum showcases some of the saved buildings, but also highlights the pain of the community’s loss. Upper Canada Village also showcases saved buildings, but encourages visitors to immerse themselves in the 19th century and remember life as it once was.

Although different in their mandate, both museums contain buildings from communities that are now under the waves of the St. Lawrence. The buildings are also filled with furniture and artifacts dating from different time periods and belonging to various families. With so many objects from disparate places, many people aren’t surprised to learn that the museums could be haunted. Whether spirits have attached themselves to their beloved homes or artefacts that were removed, or they remain tied to the land that was lost, visitors and staff at both museums have reported numerous spooky encounters. In fact, the Lost Villages Museum has so many documented cases of the paranormal, it is regularly opened for investigations and Upper Canada Village is a popular site for the Haunted Walk during the summer months.

Encounters with the Unknown

While uncanny encounters in the area of the lost villages have risen since the mid 20th century, these strange sightings didn’t start with the flooding. In fact, some believe that people in the area might have had an encounter with the unknown in the mid 19th century. Recounted to the CBC nearly a century after it happened, the event occurred on the island of Milles Roches, a lost village in the middle of the St. Lawrence. Strange lights were spotted by two people near a farm where two elderly residents remained totally oblivious to the odd sight. It was later determined that other people had witnessed the same lights. Although it was accompanied by no sounds, this phenomenon happened for several weeks afterwards and the number of sightings increased. While the lights eventually stopped, the folklore surrounding the tale did not. This was a time long before electricity and no one has found an adequate explanation for these strange orbs. Researchers are still baffled if this might be a case of the paranormal or, perhaps, UFOs.

Whatever the cause, lights are still spotted in the area of the St. Lawrence lost villages. In fact, dancing lights under the surface of the water are reported by boaters and people on the shore, often around the former villages. Unexpected shadows are sometimes seen in the water, and people describe a disturbing quiet that occasionally descends over the shoreline. Faint voices and sounds on the water are also reported, often interpreted as eerie reminders of the sunken communities below the surface.

With so much displacement and unsettlement, it’s no wonder that people have felt uncomfortable here. The strange sensation of something unseen or the discomfort of an annoyed presence is felt by many. Perhaps these are community members, still displeased over the flooding of their communities. Maybe it’s the graves of early settlers that were likely displaced during the flooding; while many remains were moved, countless other unmarked or forgotten graves would have been missed. Or perhaps it’s the area, steeped in history and filled with community spirit, that draws the paranormal to the site. Whatever the reason, the lost villages of the St Lawrence continue to allure people to this day, many of whom now recognize the terrible trauma of losing entire communities to the waters of the great river.

Written by:

Brittney Anne Bos, PhD

Haunted Walk Tour Guide & Host

Sources:

John Robert Colombo, Mysteries of Ontario, 1999.

https://spectrum.library.concordia.ca/981759/1/O%27Flaherty_PhD_F2016.pdf

https://www.toronto.com/news-story/9389924–lost-villages-come-back-to-life-for-perth-high-school-students/

https://www.cbc.ca/archives/entry/st-lawrence-seaway-let-the-flooding-begin

https://interestingengineering.com/aultsville-the-village-that-was-burned-to-the-ground-for-science

https://www.britannica.com/topic/Saint-Lawrence-Seaway

https://www.hilltimes.com/2017/08/09/lost-villages-monument-need-citizen-activism/115566

https://globalnews.ca/news/4369620/lost-villages-of-the-st-lawrence-river-canadas-atlantis/

http://bbergem.com/lostvillagesmuseum

https://www.thenewshouse.com/borderlines/unforgotten-memory-lost-village-cornwall-seaway/