It’s a Sunday afternoon in a small side-room at the Canadian Museum of History in the Nation’s capital. Outside, it’s sunny and hot, and the choppy waters of the mighty Ottawa River are sparkling. But inside, the atmosphere is a little more sombre. I’ve come to pay my respects to the dead. Not anyone I know, per sae, though I have been introducing them to people for the past 16 years. “The forgotten and misplaced dead,” is how I refer to them when guiding the Original Haunted Walk of Ottawa. “Here, beneath our feet.” Yet when human remains were discovered during digging for the Ottawa Light Rail Transit system along Queen Street (between Metcalfe and Elgin) in 2013, most people were very surprised.

Yes, says Ben Mortimer, Senior Archaeologist with the Paterson Group, “The cemetery was perceived as being unknown, or that people didn’t know it was there. But I say it was unknown to everybody except archaeologists, history buffs, and people who had done The Haunted Walk of Ottawa.”

Listen Ben Mortimer’s comments:

The Facts:

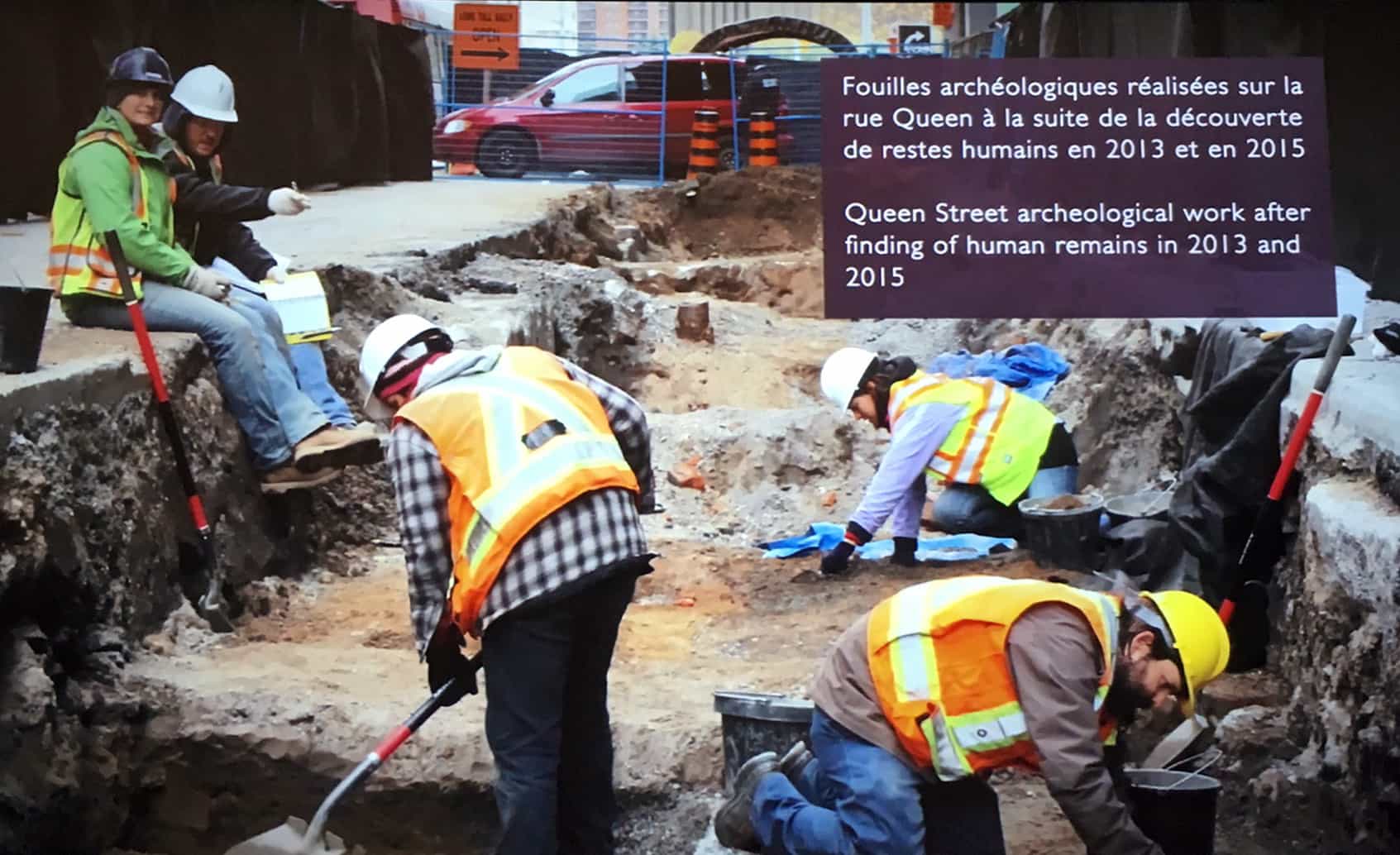

- human remains were found during digging under Queen St. in 2013

- found were 19 relatively intact burials and thousands of bone fragments from dozens of disturbed burials

- the remains are from early 19th century interments in Barrack Hill Cemetery, Ottawa’s first burial ground

- that cemetery closed in 1845 and the growing city soon engulfed the site

- complaints of “floating vapours” was one of the reasons the overly-full cemetery was closed

- over 500 people were originally buried in this cemetery

- in total, the buried remains of 79 individuals were found (32 children, 47 adults)

- some were still in their original resting places, buried on their backs, heads to the west, in rows, in coffins—all typical of Christian burial practices

- the remains will be been reinterred, with private burial services, at Beechwood Cemetery

- a permanent memorial plaque will be erected at the new burial site

In 2014, the Paterson Group were brought in to conduct an archaeological survey of the area and then disinter the remains, handing them off to the Canadian Museum of History for analysis. Now, years later, the remains have been studied, the data collected, and they are ready to be reinterred, this time in Beechwood Cemetery. But first, a public visitation and a chance for today’s citizens of Ottawa to pay their respects to some of the city’s earliest settlers.

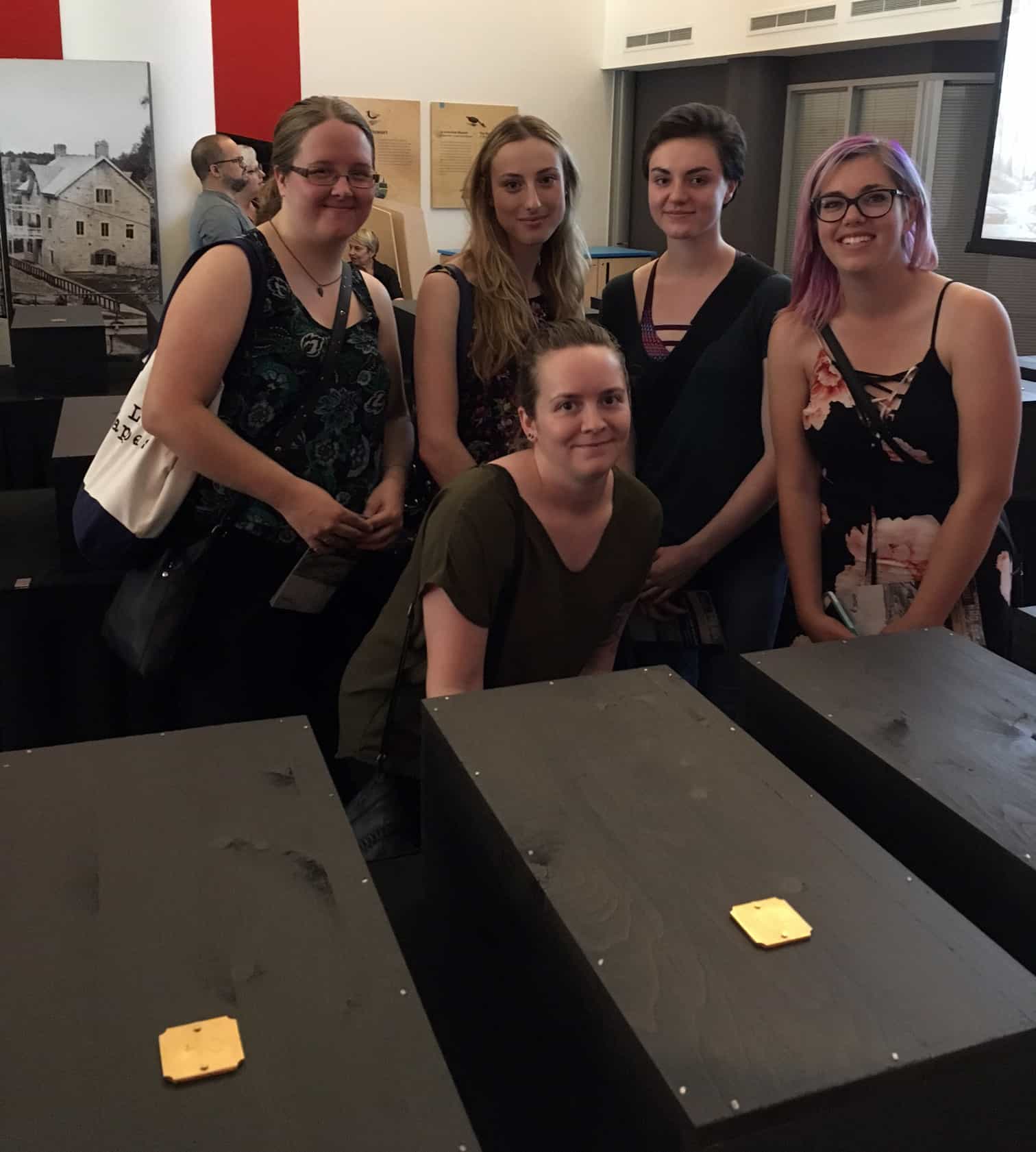

I don’t know what I was expecting, but it wasn’t this. Perhaps I thought that, being in a museum, it would seem more like a museum exhibit. But it doesn’t. Not at all. The moment you walk in the room and see the small, black wooden caskets laid out row upon row, you can’t help but stand in silence for a moment and take it all in. “This is surprisingly moving,” says Virginia, a visitor, who stops and raises her hand to her heart as she looks around. I agree with her. This isn’t a museum exhibit, it’s an actual funeral visitation—complete with guest book and classical music softly playing—and these unknown dead are being treated with as much respect as any honoured dead might be.

52 Caskets Hold the Remains of 79 Individuals

There are 52 caskets containing the remains of 79 individuals (those remains which were found buried together will remain together). The caskets are small, some of them heartbreakingly so. They are made of pine, painted a dull black, with single brass nameplates tacked onto them bearing only a hand-stamped number. The team have researched Victorian funerary practices and have tried to match them as well as they could. Even the remains inside the boxes have been wrapped in muslin, reflecting the practice of the funeral shroud. Later when the caskets are brought to Beechwood Cemetery to be reinterred, private burial services will be held with the same hymns, verses, and prayers the Victorians likely would have used when these dead were first laid to rest.

“I like to think we are repairing a dignity deficit for these folks,” says Paul Henry, Chief Archivist with the City of Ottawa. And indeed, these individuals and their remains have had a rough go of it. When the Barrack Hill Cemetery was closed in 1845, many of the buried dead were claimed by their families and reburied at the Sandy Hill Cemetery (which, by the way, in turn was closed in 1911, becoming Macdonald Gardens Park, and the bodies—well, at least most of the bodies—were moved again, this time to Beechwood Cemetery). Those left behind when the two-acre Barrack Hill Cemetery was closed were probably those whose families did not claim them. But why? Perhaps they couldn’t afford the cost, perhaps they’d moved away from the area and never heard news of the cemetery’s closing, or perhaps, more than likely, the entire family had died of disease in one of the town’s many early epidemics and there simply was no one left to claim them.

So there they remained, the town turning into a city, roads laid out and buildings built right on top of the forgotten cemetery. The archaeologists found evidence that as digging occurred in the area over the years (to lay water mains, or other services), it was clear that occasionally old burials had been disturbed, and many times remains were simply “redeposited on site, mixed with fill, and so this resulted in a lot of small bone fragments,” says Mortimer. Thousands of them, actually.

All of these thousands of fragments, along with the intact remains, were sorted and examined by Dr. Janet Young, Curator, Physical Anthropology, Canadian Museum of History. Life for the early European settlers in the region was brutally difficult, something that shows in their bones, she tells me. In her analysis of the remains, Dr. Young relates she found evidence of lifelong struggles with bad health, poor nutrition, tooth decay, and disease. Undeniable evidence of a high infant mortality rate was also found. Of the 79 individuals recovered, 32 of them were children or babies.

Listen to Margo’s Conversation with Dr. Young:

But who were they? Do we have any evidence as to their identities? The answer is not really, according to Mortimer, and this points to the socio-economic status of these individuals. “These are families who don’t have a lot, so they’re not going to bury someone with anything that can be reused,” he explains, things like garments, shirts, and shoes. “We found no evidence of footwear in any of the burials,” he tells me, and I take a moment to wonder why I find that so sad.

Well then, apart from bones, just what did they find? A few buttons, some hairpins, lines of straight-pins down the centre of torsos (most likely indicating the individual had been wrapped in a shroud of muslin or cotton which was then pinned closed), and a few copper nails which had clearly held nameplates onto coffin lids at one point (but the nameplates had been removed before burial, most likely by grieving parents wanting a final keepsake of their child).

And the coffins themselves? It’s true that one of the things I expected to see here today were the original coffins from the “intact burials” I’d heard they’d discovered. Turns out an archaeologist’s idea of “intact” is a bit different from mine. “The coffins, while still visible, were completely collapsed and pancaked onto the remains,” explains Mortimer. “So remains and coffins together, in every instance, were 5cm to 10cm thick from top to bottom, really squished.” The coffin lids had formed to the skeleton in a thin layer which could be peeled off, he says.

Listen to Ben Mortimer’s description of what they found:

Haunted Walk Tour Guides

Looking around the room, I feel a sense of relief that these individuals have been found and given some sort of identity, even if it is just a number and a detailed scientific report. Chief Archivist, Paul Henry, agrees, saying it’s more of an identification than they’d had before, laying forgotten beneath a city street. “Do you believe in ghosts?”, I ask. “Well, that’s the question, isn’t it?”, he replies. But since I believe an archivist deals with “ghosts” every day, I don’t press him. He does tell me, however, that there has been no haunting activity associated with the remains, that “all has been peaceful”, and we agree these lost dead must simply be relieved to have been found and acknowledged.

But wait, have they all been found? The consensus among the experts is no. These remains were found on public land, but there were some recently found on private land in the area and those remains are now being analyzed. Dr. Young tells me she fully expects more remains will be found and so they are still monitoring as more excavation work is being done in the area. So, it seems, it’s fair to say that although many have now once more been laid to rest, many of the forgotten and misplaced dead still lie beneath our feet as we guide our tours through the busy streets in the old Barrack Hill Cemetery site, only one block away from Parliament Hill.

Take a video tour with our Creative Director, Jim Dean, of one of the locations where the remains where discovered:

______________________

“Honouring the individuals buried at the Barrack Hill Cemetery” took place at the Canadian Museum of History, Sunday, September 24, 2017, 1:00-3:00pm.

Thanks to all the experts for taking the time to talk with us.

_____________________

Margo MacDonald has been a tour guide and researcher for the Haunted Walk since 2001, and guides tours in both Ottawa and Toronto. This is the second time Margo has been invited to attend events relating to the reinterment of lost remains found buried beneath pavement, having previously witnessed the reinterring of King Richard III (found buried beneath a carpark) in Leicester, England. You can hear her talk about that experience on episode three of the Haunted Talks podcast. You can also read her account of the Gatineau Ghost in the book “Ghosts of Ottawa”. Follow her on Twitter @margo_thespian