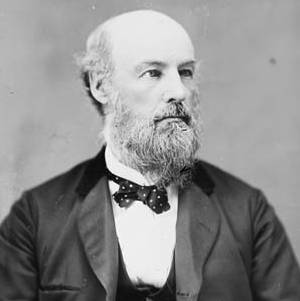

Joseph Merrill Currier was a man seemingly plagued by misfortune. At various times a lumber baron, businessman, and member of parliament for Ottawa. He was born in Troy, Vermont in 1820, and moved to Ottawa at age 17 to work in the lucrative lumber trade. Over the next twenty-five years, he built a successful business career in the Ottawa region, becoming involved in the ownership of several businesses. These included sawmills in Manotick and Hull, and his own lumber business in New Edinburgh. The crowning achievement of Currier’s life was the building of a house at 24 Sussex Drive, the official residency of the Canadian Prime Minister since 1950. Despite his early achievements he could not escape the spectre of tragedy that haunted his early life.

In 1846, Currier married Miss Christina Wilson, and the pair went on to have four children. However, nine years later, tragedy struck. Three of their young children died from scarlet fever within five days of each other, an unfortunately common cause of death among children at the time. Three years later, his wife Christina also perished, reportedly from grief.

Two years after the death of his first wife, Currier visited the Crosbyside Hotel in Lake George, New York, where he stayed for the month of August. During this period, he became close with the hotel owner’s daughter, Ann, and they married the following year. The couple were reportedly very happy, and as part of their honeymoon Currier proceeded to give his new wife a tour of his properties. This tour culminated in a visit to the mill just outside Ottawa in Manotick that Currier co-owned, now known as Watson’s Mill, which was celebrating a year of successful operation.

Ann wore a long, crinoline hoop dress for the visit, a style that was highly popular at the time – if somewhat risky. With a circumference of up to six yards, crinoline dresses were the cause of thousands of deaths. The dresses caught fire, got tangled in machinery or carriage wheels, and were even susceptible to accidents caused by a sudden gust of wind.

During their visit, Ann wandered away from Currier and the rest of the group. Her dress became caught in the Mill’s machinery. The momentum of the revolving drive shaft threw her against a support pillar, where she struck her head. She was killed instantly. Most reports of the tale describe Currier as being so distraught over Ann’s death that he sold his shares in the mill, sawing his ties to Manotick, and never returning.

However, the story does not end there.

It seems highly unlikely that Currier would simply allow his young wife to wander around a mill filled with dangerous machinery, especially given that she was wearing a long, hooped dress, prone to accidents. It is very strange that such a mistake could have been made. Not only had Currier been working in the lumber trade for two decades, but Ann herself had just spent a month touring lumber mills, and so should have been no stranger to the dangers of heavy machinery.

Lord Rosebery, a British politician (and later Prime Minister of the United Kingdom), kept journals of his visit to North America in 1873. During his time in Canada he met with Joseph Currier and his then business partners, Wright and Batson. They visited the saw mills belonging to these men, including, according to Lord Rosebery, the mill where Currier’s wife was killed. This, despite Lord Rosebery’s visit being ten years after Currier was supposed to have sold his shares in the mill, and his journals contradict the assertion that Currier never returned to the mill.

Lord Rosebery’s description of Ann’s death, though brief, also differs from the typical version of events in key ways. According to Rosebery, Anne does not die from a strike to the head. Instead, he says that “she caught in a machine and was cut to pieces before his eyes.” In Rosebery’s version of events (based on the story told directly to him by Joseph Currier), Currier himself witnesses Ann’s death. Rosebery also cites the incident as happening on their wedding day, rather than a month later.

The mysterious circumstances surrounding the conflicting tales of the events that occurred that fateful day seem suspicious at best, and sinister at worst. It is of course possible that Lord Rosebery was merely confused about events. However, it is difficult to disregard the fact that there might have been other motives at work here; murder, suicide, or a life insurance claim. There is also the possibility that Currier married Ann for her family’s fortune, particularly as, at the time of their marriage, her father had been experiencing great success in the hotel industry.

After his second wife’s death, Currier seemed to suffer setback after setback. A mill that he co-owned in Hull burned down, and he went bankrupt. Currier became a Member of Parliament but was later removed from his position after an accusation levelled at him by a young Wilfrid Laurier. Laurier accused Currier of violating conflict of interest rules, a business that he co-owned sold lumber to the government. Apparently this was without Currier’s knowledge. Regardless, he was forced to step down. Ann’s ghost has since been spotted at both Watson’s Mill, and around Parliament Hill and the nearby canal locks.

In one final interesting twist of fate, the Crosbyside hotel, owned by Anne’s family and the place where her and Currier met changed hands until it was bought by a woman from Troy, Vermont, Currier’s birthplace. It was renamed Wiawaka and became a women’s retreat, and remains so to this day.

Want to explore more of Ontario best ghost stories? Join us for a tour in Kingston, Ottawa or Toronto!

Written by Sam Gardiner